Data visualization

from a communication perspective

Miren Berasategi

with Mikel MadinaEuropean Data Incubator

Bilbao, 6th November 2019

- Data visualization as an artefact

- The atomic level

- Number of variables

- Generating new idioms

- Multiple Linked Views

- Beyond 2 dimensions

- Other senses

- Data visualization as a communication product

- What charts say

- What charts mean

- What charts do

- The artefact goes social

- Data counseling

- Responsive data visualization

1. Data visualization

as an artefact

Something to tell the data to others.

artefact (US artifact) noun

1 An object made by a human being, typically one of cultural or historical interest.

‘gold and silver artefacts’

2 Something observed in a scientific investigation or experiment that is not naturally present but occurs as a result of the preparative or investigative procedure.

‘the curvature of the surface is an artefact of the wide-angle view’

The Oxford Dictionary of English

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

Maximum data density is 1:1, and this is not usually the case:

| data points | < | pixels |

| observations |

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

Some strategies to overcome this constraint:

- Filter observations

- Split data into multiple charts

- Augmented visualizations

- Densify

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

1. Filter observations

- By design, communicating a selection of data

- By allowing users to filter according to their interests

- Innovative filtering (i.e. Smart brushing)

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

2. Split data into multiple charts

Facets, trellis, small multiples.

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

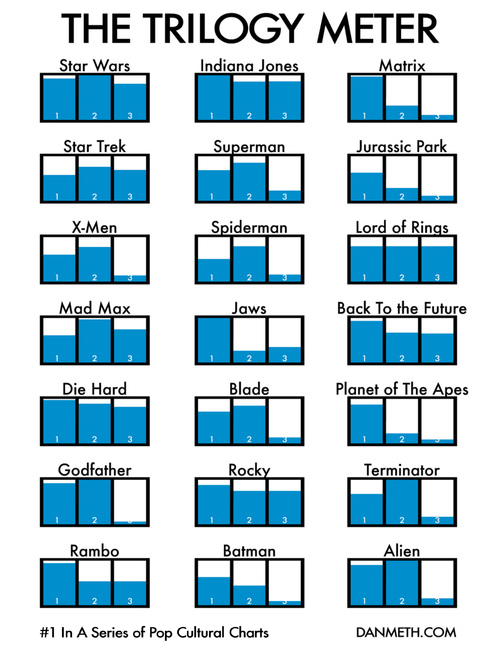

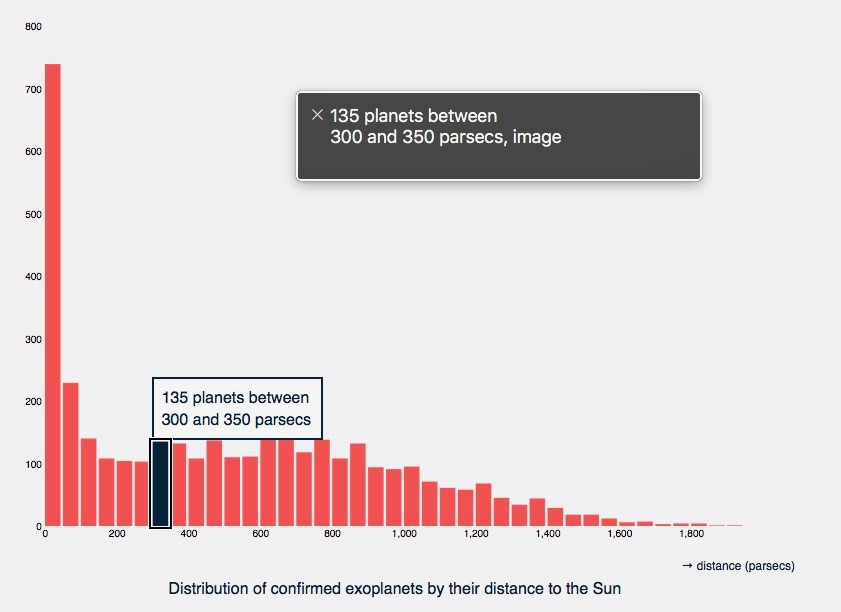

3. Augmented visualizations

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

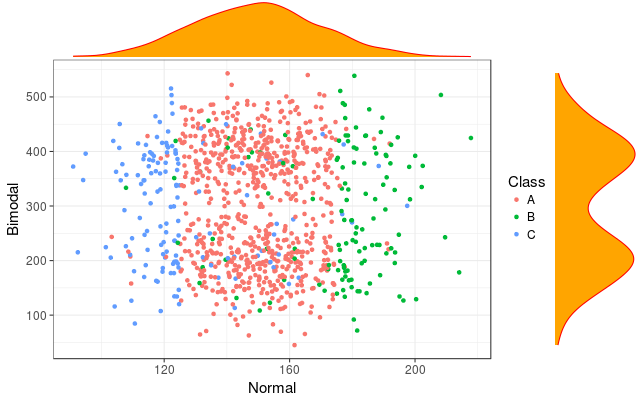

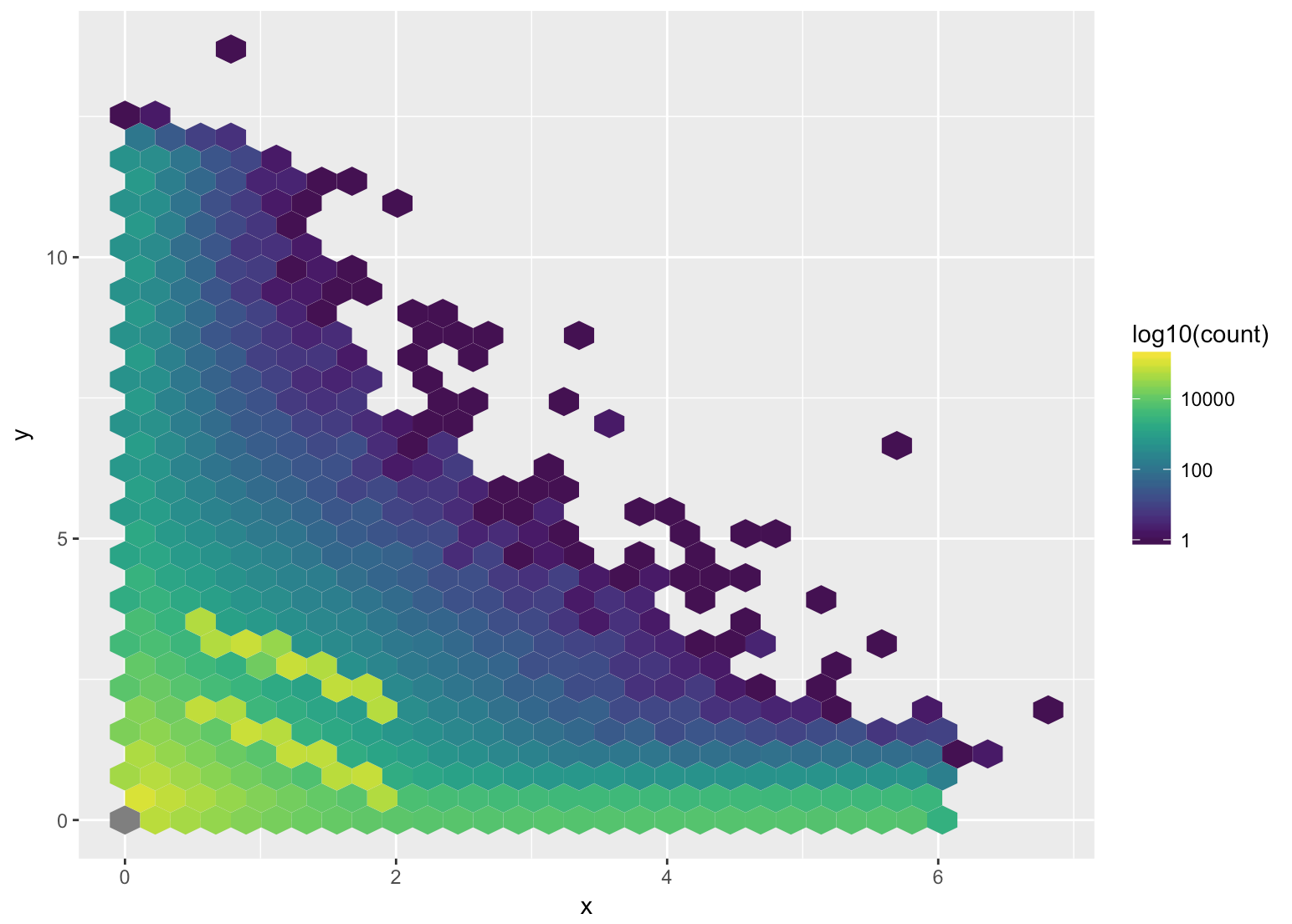

4. Densify

- Escaping overplotting in scatterplots

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

4. Densify

- Escaping overplotting in scatterplots

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

4. Densify

- Escaping overplotting in scatterplots

stat_binhex function from the ggplot2 package1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

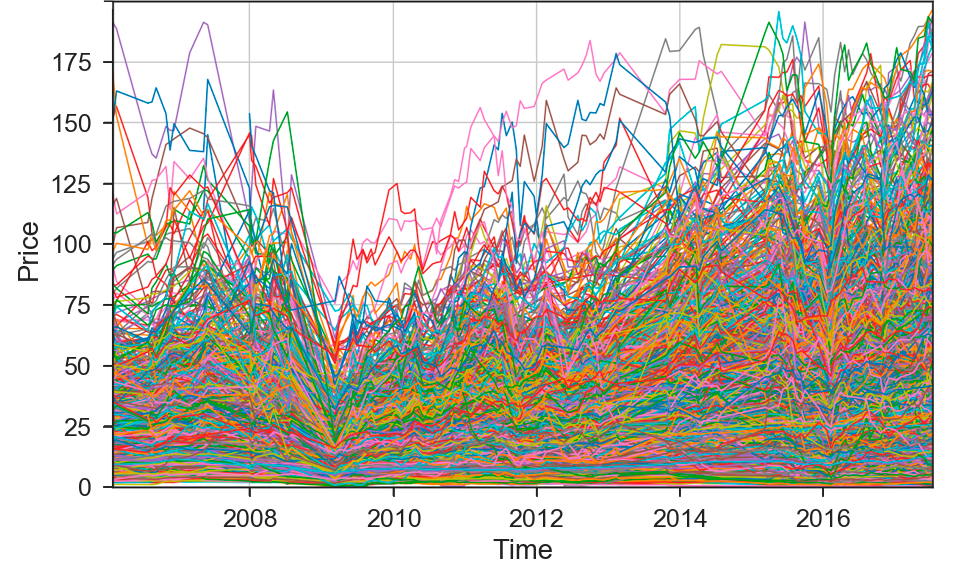

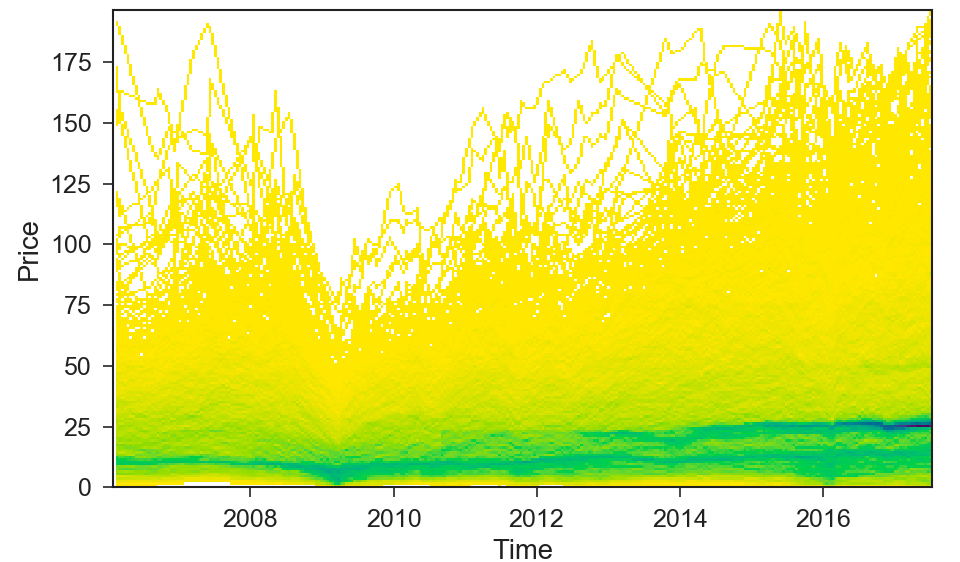

4. Densify

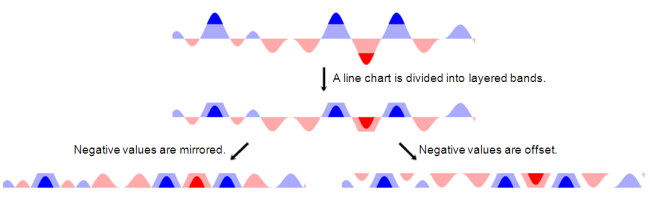

- Timelines

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

4. Densify

- Timelines

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

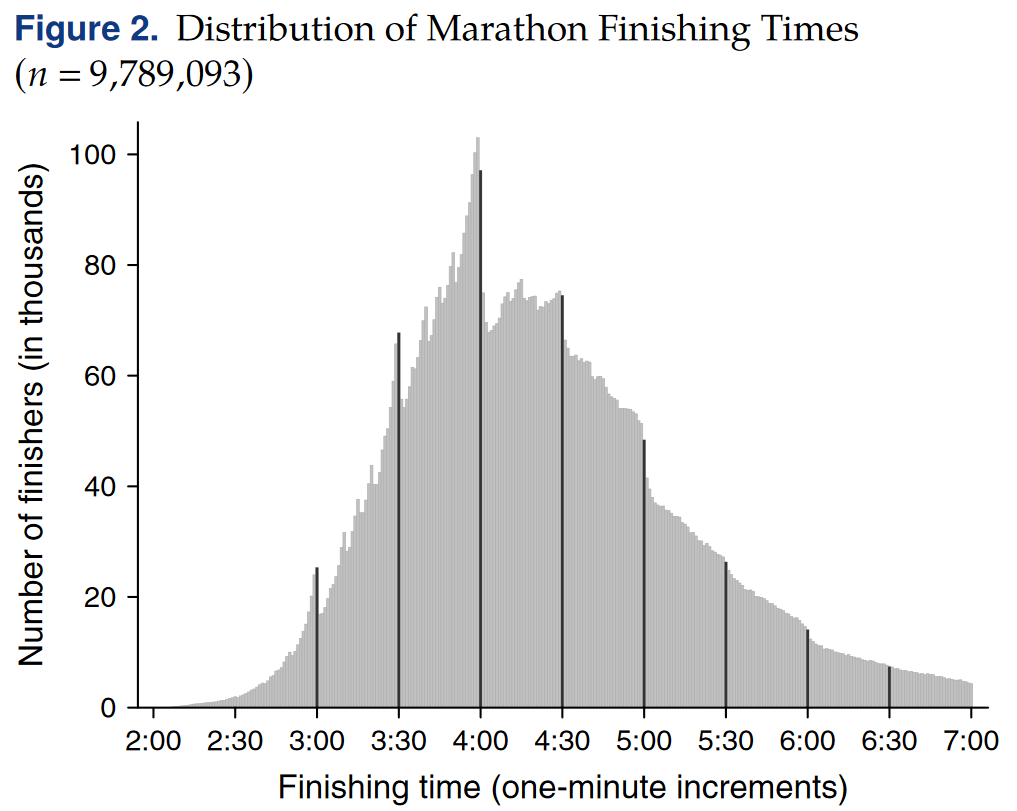

(off-topic: reference-dependent preferences)

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

A couple more things at this level of the number of observations:

- the time factor

- nothingness

- uncertainty, projections and other non-factual data

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

The time factor

- Static visualizations with real data (at the time of loading)

- Real-time visualizations, static and auto-refreshed

- Streaming data visualizations showing the flow of data

Require an additional effort for operational intelligence, where immediate decision making could be a requirement.

Source: Aragues 2018

There is more time than real-time.

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

The time factor

A note of caution on using animations:

- They rely on memory (from one frame to the next), so change should be obvious

- Users needs to find the area of interest on their own, so they may miss the point (selective attention)

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

How to communicate nothingness? (Kirk 2014)

- Null Absence of measurement

- Zero Absence of amount/magnitude

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

How to communicate nothingness?

- Null Absence of measurement

- Zero Absence of amount/magnitude

- Blank Try to use nothing to represent something

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

How to communicate nothingness?

- Null Absence of measurement

- Zero Absence of amount/magnitude

- Blank Try to use nothing to represent something

- The design should be invisible

1. Data visualization as an artefact The atomic level

Communicating uncertainty, projections,

and other non-factual data is challenging.

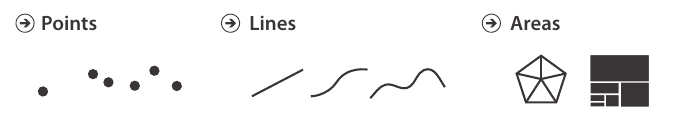

1. Data visualization as an artefact Number of variables

A mark is a basic graphical element in an image.

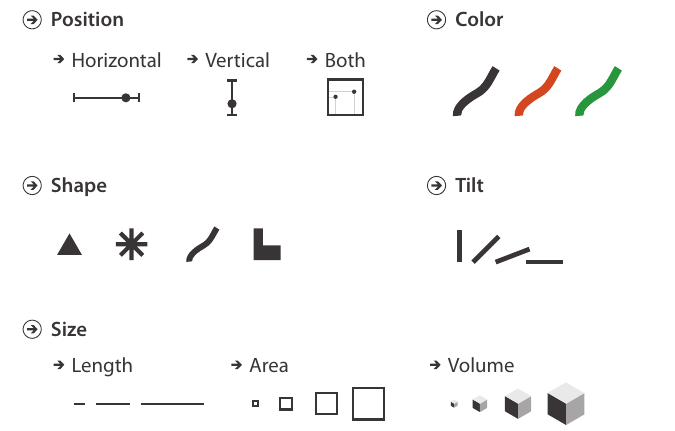

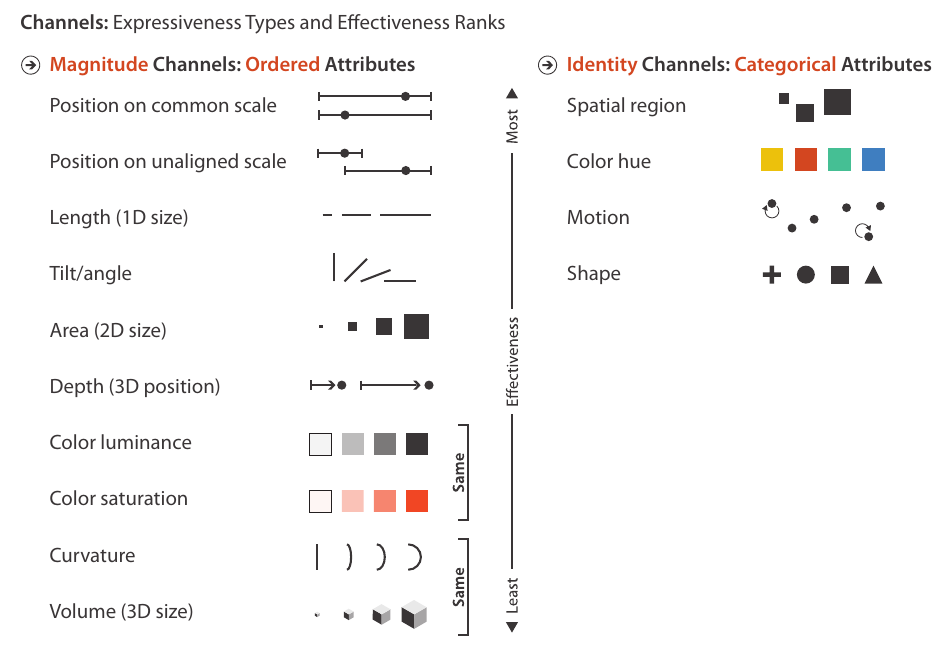

1. Data visualization as an artefact Number of variables

A visual channel is a way to control the appearance of marks.

1. Data visualization as an artefact Number of variables

It is required to reduce dimensionality (statistically): PCA, factors, clustering.

1. Data visualization as an artefact Number of variables

1. Data visualization as an artefact Generating new idioms

A word of caution:

- will need to be custom coded

- readers will require training

- correct interpretation may be more time demanding

Xenographics: Weird but (sometimes) useful charts

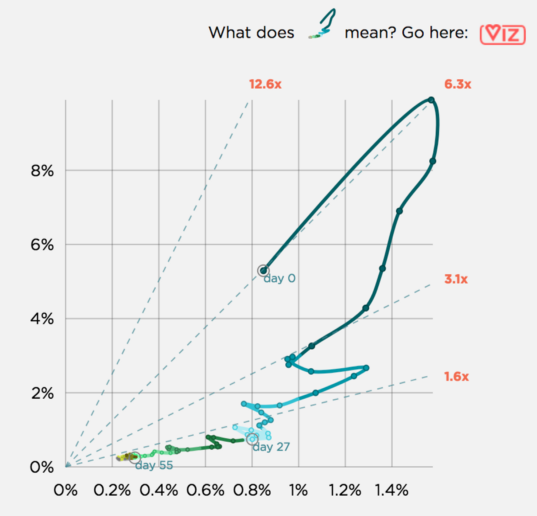

1. Data visualization as an artefact Generating new idioms

1. Data visualization as an artefact Generating new idioms

1. Data visualization as an artefact Multiple Linked Views (MLV)

In a MLV system, a dataset is shown in multiple simple visualizations, with the data items shown in the different charts corresponding to each other. The charts in each visualization can be used to highlight, control, or filter the data items shown in the others.

(Meyer & Fihser 2018)

(Lagner, Kister & Dachselt 2019)

1. Data visualization as an artefact Beyond 2 dimensions

virtual / augmented reality

1. Data visualization as an artefact Other senses

1. Data visualization as an artefact Other senses

2. Data visualization as

a communication product

Something to tell the data to others.

2. Data visualization as a communication product

The modern approach to data visualization is focused on quickly making data visualization.

(Meeks 2018)

2. Data visualization as a communication product

Focus on speed affects:

- how data visualization products are designed

- what tools are used to create them

- the role of the creator in relation to the product

- how engagement with readers in envisioned

2. Data visualization as a communication product

Ultimately, data visualization is not a technical problem, it’s a design problem and, more than that, a communication problem.

(Meeks 2018)

Let’s look at what charts say, mean, and do.

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts say

Explicitly

Charts do “show me the data” (actually, it’s more that they tell the data than actually show it).

Means choosing the right specific chart to use in order to display and query the data.

How to improve: Expose data cleanly and clearly. Aim for either query or validation. Distinguish accuracy vs. precision.

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts say

Implicitly

No chart is an unbiased view of the data, as data visualization is a manufactured artefact.

All data is transformed to be in a chart, and the inaction of not designing that transformation carries just as strong an implication as the action of transforming it.

(Meeks 2018)

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts say

|

|

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts say

Implicitly

The implicit channel of a data visualization (the title and other framing elements) can be even more powerful than the explicit channel.

How to improve: Style should be intentional, purposeful and thematically appropriate, not the result of defaults or superficial decisions.

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts say

About the underlying system

[…] all charts display data and all data is a proxy for the systems that created and measured that data.

(Meeks 2018)

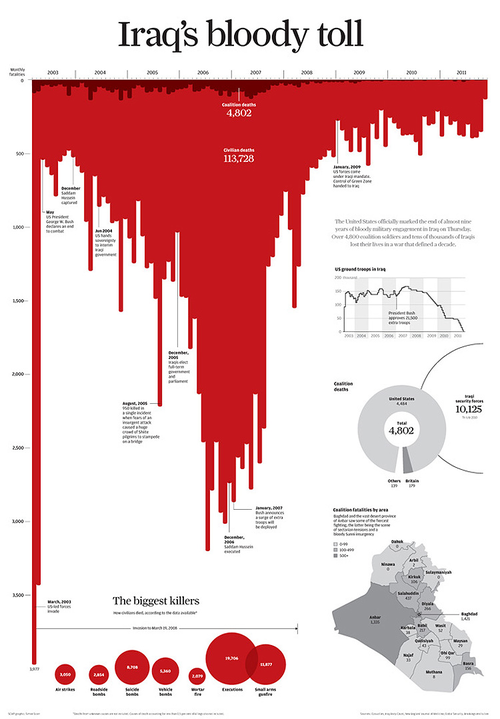

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts say

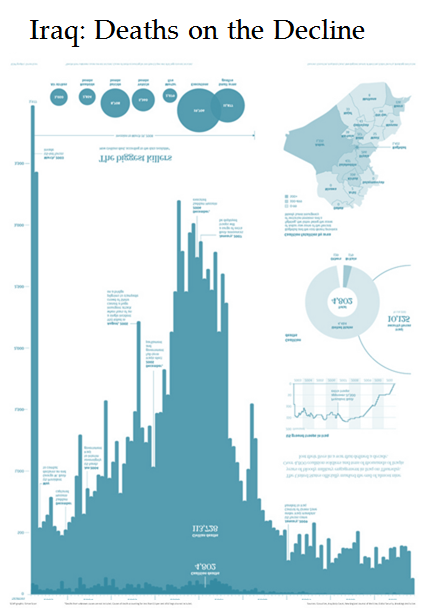

About the underlying system

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts say

About the underlying system

[…] all charts display data and all data is a proxy for the systems that created and measured that data.

(Meeks 2018) How to improve: Caution not to reveal an underlying system that is proprietary or confidential.

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts say

Descriptively

- internally: axes, labels, annotations

- externally: surrounding text, figure descriptions, discussions

Unlike the implicit channel, the descriptive channel is active and purposeful (not subconscious).

How to improve: Consider annotations, labels, axis elements as part of the data visualization.

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts say

By being more explicit in our own understanding of what charts say and how we can systematically describe what they say, we can grow more capable of using the channels available in that expression to our advantage.

(Meeks 2018)

What does your chart say that you didn’t intend?

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts mean

Intentionally

The mode and purpose of a chart should be well understood by the chart maker and immediately apparent to the chart reader.

(Meeks 2018)

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts mean

Historically

Charts are products of their time.

It is important to provide background about the data sources, to enable checking whether they are still based on relevant priorities, dimensions and metrics.

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts mean

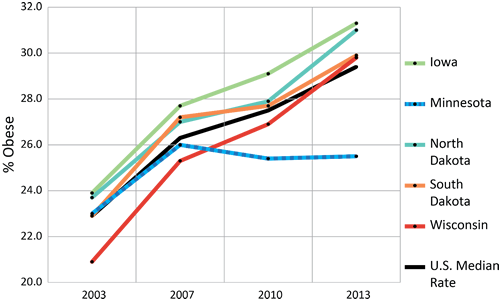

Historically

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts mean

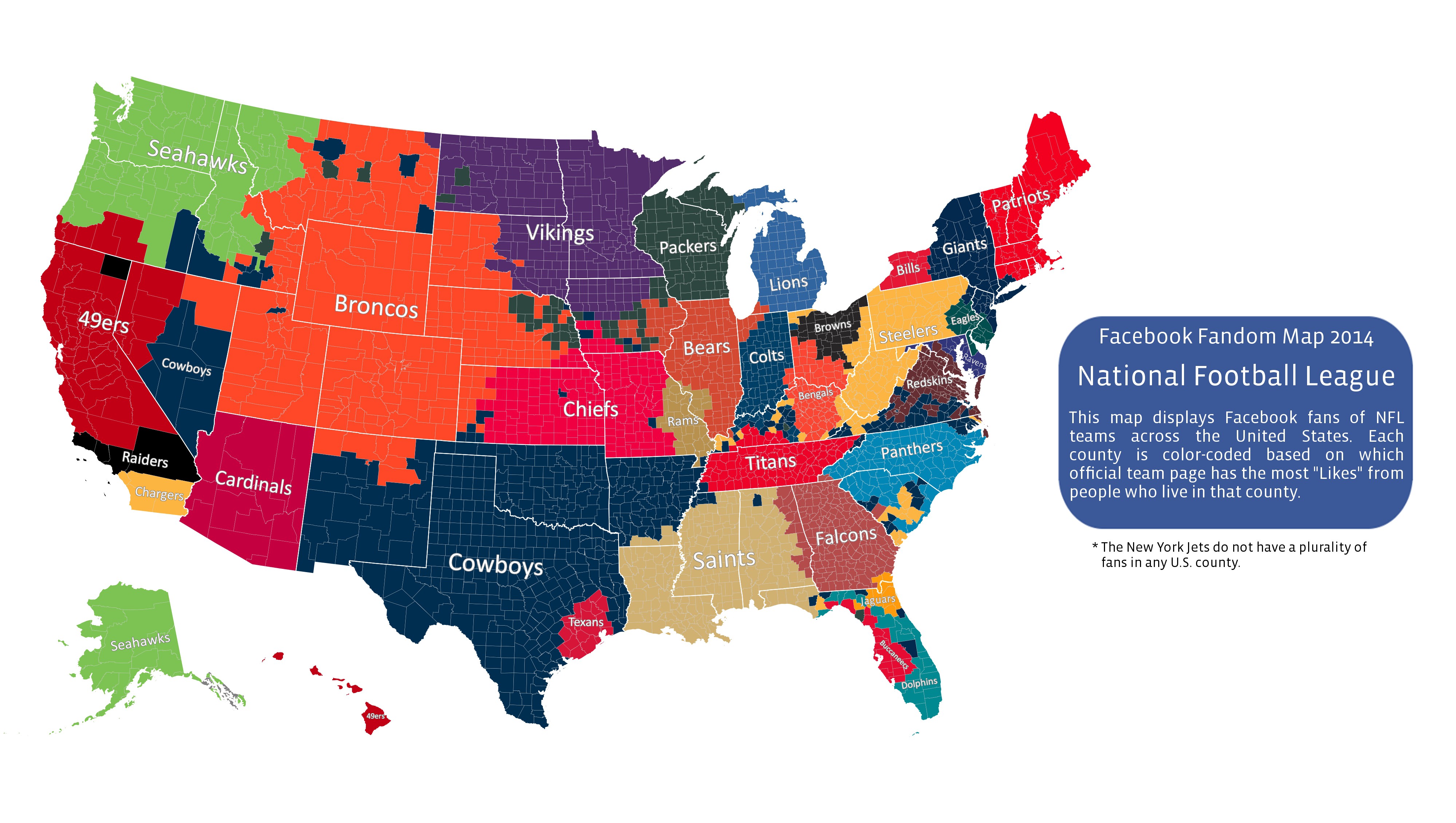

Culturally

Charts should be adapted to the culture they will be consumed in.

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts mean

Contextually

A chart might end up serving as context: design and provide a version of the chart that is suitable for inclusion alongside other charts.

Enable removing and adjusting data visualization elements to reduce complexity, not based on screen size as in responsive data visualization, but on priority.

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts mean

Meaning-making may sound too soft to the kind of technical professionals that make and read data visualization but communication without meaning is just noise.

(Meeks 2018)

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts do

The most important thing about a chart is its impact.

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts do

Provide insights

Identify and emphasize the insights that the readers might expect.

which may be considered insights by an audience (Meeks 2018)

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts do

Cause change

As difficult to measure as it is important.

How have they impacted business decisions? How were they used in presentations? Where they modified (changed colours, cropped, annotated) somehow?

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts do

Cause visual literacy

All data visualization was, at some point, complex data visualization, until an audience grew comfortable and literate enough to read it.

(Meeks 2018)

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts do

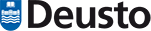

Cause visual literacy

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts do

Create new charts

2. Data visualization as a communication product What charts do

All communication is evaluated based on content, but persuasive communication, which is all data visualization unless it is purely decorative, is rightly also evaluated based on effect.

(Meeks 2018)

3. The artefact

goes social

Something to tell the data to others.

3. The artefact goes social Data counseling

[…] brings domain expertise into the operationalization process to help inform decisions about good proxies as well as to uncover insights using the resulting visualizations.

(Meyer & Fisher 2018)

3. The artefact goes social Data counseling

Based on interviews (1) for

- gaining an understanding of the questions and data

- get feedback on proxies, explorations, and visualization prototypes (2)

3. The artefact goes social Data counseling

Interviews

The role of the interviewer is to ask questions that will guide the stakeholders toward elucidating the information necessary for working through an operationalization process and designing visualizations.

(Meyer & Fisher 2018)

3. The artefact goes social Data counseling

Interviews

Identify stakeholders:

- analysts

- data producers

- gatekeepers

- decision makers

- connectors

3. The artefact goes social Data counseling

Interviews

Require practice and experience.

Semistructured: be prepared, but also be open.

- start with open ended questions (problem, data, context)

- use the conversation to search out the more abstract question

3. The artefact goes social Data counseling

Interviews

Use traditional conversation / interpersonal communication skills to prevent dead ends: keep them talking

- rephrase responses back

- ask the same or similar questions in different ways

- explore a completely different conversational topic

3. The artefact goes social Data counseling

Interviews

Contextual interviews

- take place in the stakeholder’s work environment

- consist of demonstrations of the tools and data inspection methods currently in use

3. The artefact goes social Data counseling

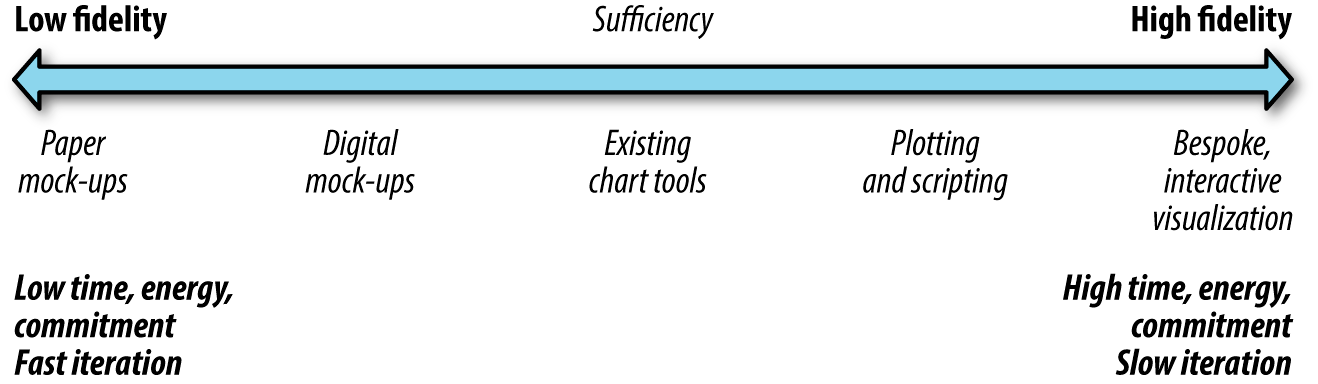

Rapid prototyping

[…] is a process of trying out many visualization ideas as quickly as possible and getting feedback from stakeholders on their efficacy.

(Meyer & Fisher 2018)

3. The artefact goes social Data counseling

Rapid prototyping

≠ fast data visualization

≈ agile/lean methodologies

and user-centered design

3. The artefact goes social Data counseling

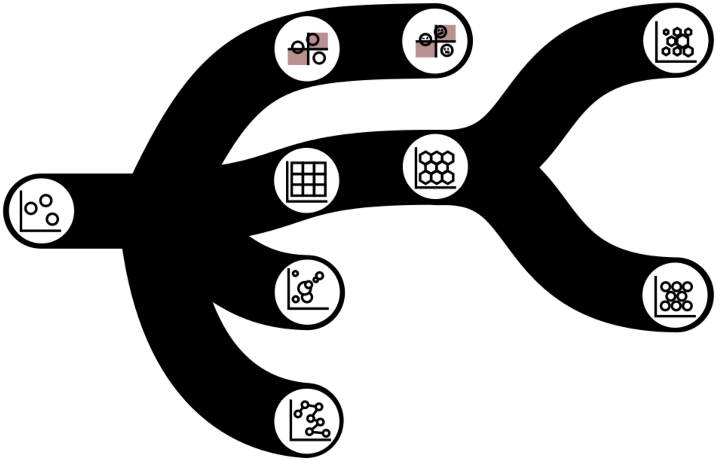

Rapid prototyping

3. The artefact goes social Data counseling

Rapid prototyping

Prototypes are made to obtain feedback on them: get to the stakeholders early and often.

Focus not on whether they like it or not, but rather on what the visualization can and cannot do (contextual interview where the stakeholder uses the visualization).

3. The artefact goes social Responsive data visualization

Responsive web design, and responsive data visualization are not simply a way to make our content accessible on smaller screens. We need to build an ergonomic web that feels natural regardless of device type.

(Hinderman 2018)

3. The artefact goes social Responsive data visualization

Unknowns require adaptability.

- the context in which the user is trying to consume the visualization

- changes in the data that is being displayed

3. The artefact goes social Responsive data visualization

Output side (the client)

Making things work in all screen types by redrawing charts to fit its container.

Match CSS breakpoints + add any new ones as the content requires: group data to fit (trade-off precision for reduced rendering complexity and performance).

3. The artefact goes social Responsive data visualization

Input side (the data)

Adapting at breakpoints. No need to just redraw the exact same elements:

As long as the message being conveyed by the data is the same, and the point you’re trying to prove is always present, you should prove it with as much firepower as you have available.

(Hinderman 2018, p.361)

3. The artefact goes social Responsive data visualization

Input side (the data)

Adapting at interaction points.

[…] present a rational default but enable users to dig into more complex or specific layers of data when the device’s capabilities limit the presentation of both at the same time.

(Hinderman 2018, p.362)

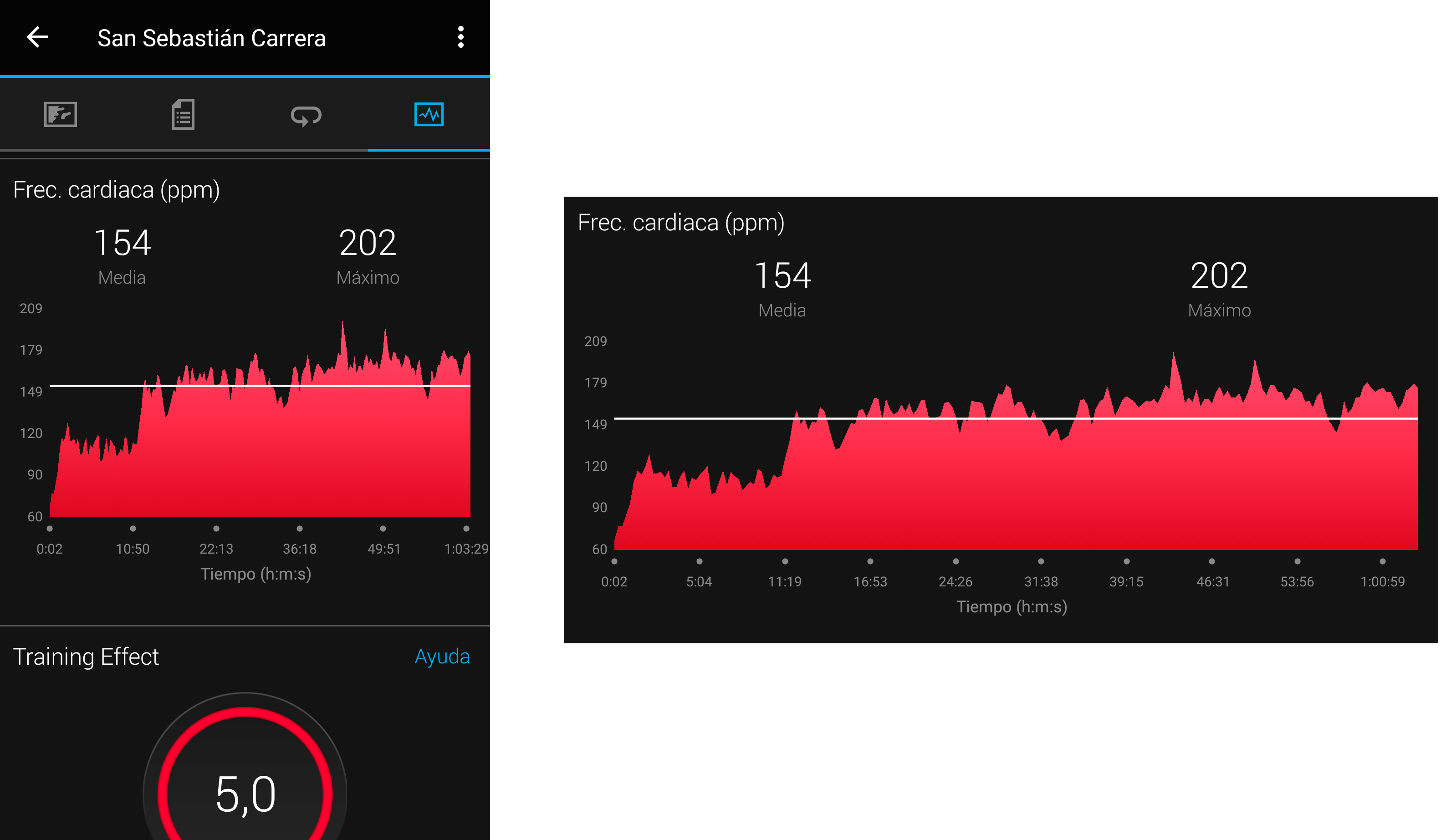

3. The artefact goes social Responsive data visualization

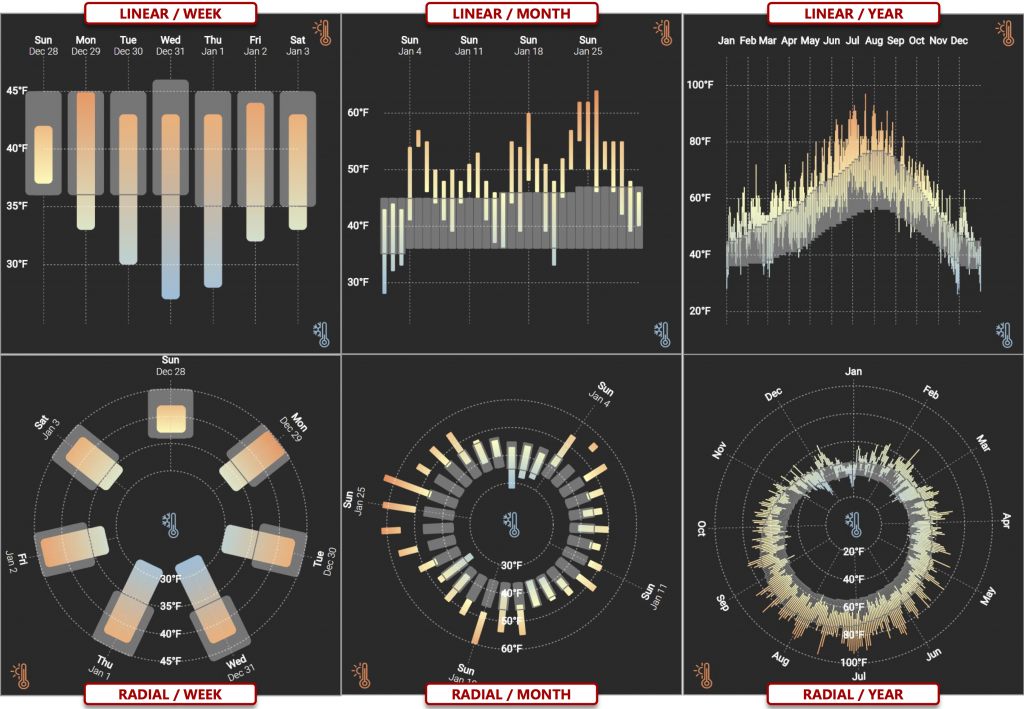

Different views on heartrate depending on device:

3. The artefact goes social Responsive data visualization

Different views on heartreate depending on device:

3. The artefact goes social Responsive data visualization

Different views on heartreate depending on device:

3. The artefact goes social Responsive data visualization

Epilogue

Thank you!

This presentation is available at

https://mrn.bz/EDI2019

Resources

- D3.js

A JavaScript library for manipulating documents based on data. D3 helps you bring data to life using HTML, SVG, and CSS. - ggplot2

Data visualization package for the statistical programming language R. - IEEEVIS 2019

Conference on Scientific visualization, Information visualization and Visual Analytics. Papers from the 2019 edition. - matplotlib, seaborn

Just two of the many data visualization libraries available for Python - Open Access Vis

A collection of open access visualization research at the VIS 2018 conference. - Xenographics

Weird but (sometimes) useful charts. - Data visualization Catalogue

A library of different information visualization types.

References

Eric J. Allen, Patricia M. Dechow, Devin G. Pope, George Wu (2017) “Reference-Dependent Preferences: Evidence from Marathon Runners”. Management Science 63(6):1657-1672. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2417

Anthony Aragues (2018), Visualizing Streaming Data. O’Reilly Media

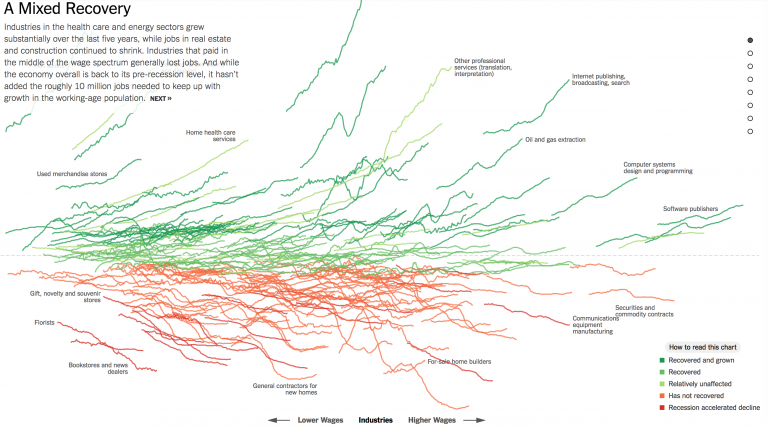

Jeremy Ashkenas & Alicia Parlapiano (2014), "How the Recession Reshaped the Economy, in 255 Charts" in TheUpshot at The New York Times

Tanja Blascheck, Lonni Besançon, Anastasia Bezerianos, Bongshin Lee, Petra Isenberg (2019). “Glanceable Visualization: Studies of Data Comparison Performance on Smartwatches”. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 25(1) 10.1109/TVCG.2018.2865142`

Matthew Brehmer, Bongshin Lee, Petra Isenberg, Eun Kyoung Choe (2019). “Visualizing Ranges over Time on Mobile Phones: A Task-Based Crowdsourced Evaluation”. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 25(1) 10.1109/TVCG.2018.2865234

Brendan Gregg (2016), “The Flame Graph”. ACM Queue 14(2)

Luc Guillemot (2018), “How Does This Data Sound?”

Jeffrey Heer, Nicholas Kong, Maneesh Agrawala (2009), “Sizing the Horizon: The Effects of Chart Size and Layering on the Graphical Perception of Time Series Visualizations”. ACM Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI), pp. 1303 - 1312 10.1145/1518701.1518897

Bill Hinderman (2015), Building Responsive Data Visualization for the Web. O’Reilly

Christophe Hurter, Nathalie Henry Riche, Steven M. Drucker, Maxime Cordeil, Richard Alligier, Romain Vuillemot (2018), “FiberClay: Sculpting Three Dimensional Trajectories to Reveal Structural Insights”, IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 25(1)

Alex Kale, Francis Nguyen, Matthew Kay, Jessica Hullman (2019), “Hypothetical Outcome Plots Help Untrained Observers Judge Trends in Ambiguous Data”, IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 25(1)

Andy Kirk (2014), “The Design of Nothing: Null, Zero, Blank”, OpenVis Conference 2014

Ihor Kovalyshyn (2017), “When Scatter Plot Doesn’t Work”

Ricardo Langner, Ulrike Kister, Raimund Dachselt (2019). “Multiple Coordinated Views at Large Displays for Multiple Users: Empirical Findings on User Behavior, Movements, and Distances”, IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 25(1) (proc. InfoVis 2018) 10.1109/TVCG.2018.2865235

Elijah Meeks (2017), “Strategic Innovation in Data Visualization Will Not Come From Tech”

— (2018), “Data Visualization, Fast and Slow”

Dan Meth (2009), “The Trilogy Meter”

Miriah Meyer & Danyel Fisher (2018), Making Data Visual. O’Reilly Media

Dominik Moritz and Danyel Fisher (2018), “Visualizing a Million Time Serieswith the Density Line Chart” arXiv:1808.06019v2 [cs.HC]

Tamara Munzner (2015). Visualization Analysis and Design. CRC Press

Jonas Schöley (2018), “Choropleth maps with tricolore”

Daniel J. Simons (2010), “Monkeying around with the gorillas in our midst: familiaritywith an inattentional-blindness task does not improve thedetection of unexpected events”, i-Perception, vol.1, pp. 3–6 10.1068/i0386

Ronell Sicat, Jiabao Li. DXR: A Toolkit for Building Immersive Data Visualizations

License

Copyright © 2019 University of Deusto

This work (except for the quoted images, whose rights are reserved to their owners) is licensed under the Creative Commons “Attribution-ShareAlike” License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/